Projects with concurrently working contributors and complex contribution schemes are common. Version control systems grant granular control over how project updates are integrated or discarded into different versions of the project. Originally designed to manage updates to the Linux kernel, git is a simple yet powerful tool used to manage these sorts of projects. The management of a git project, or repository, is facilitated in large part by three git commands:

git-commitallows workers to save the current state of their workgit-mergeallows workers to merge their work with another set of work and resolve copy conflicts, andgit-branchallows workers to create a new copy from an existing set of work.

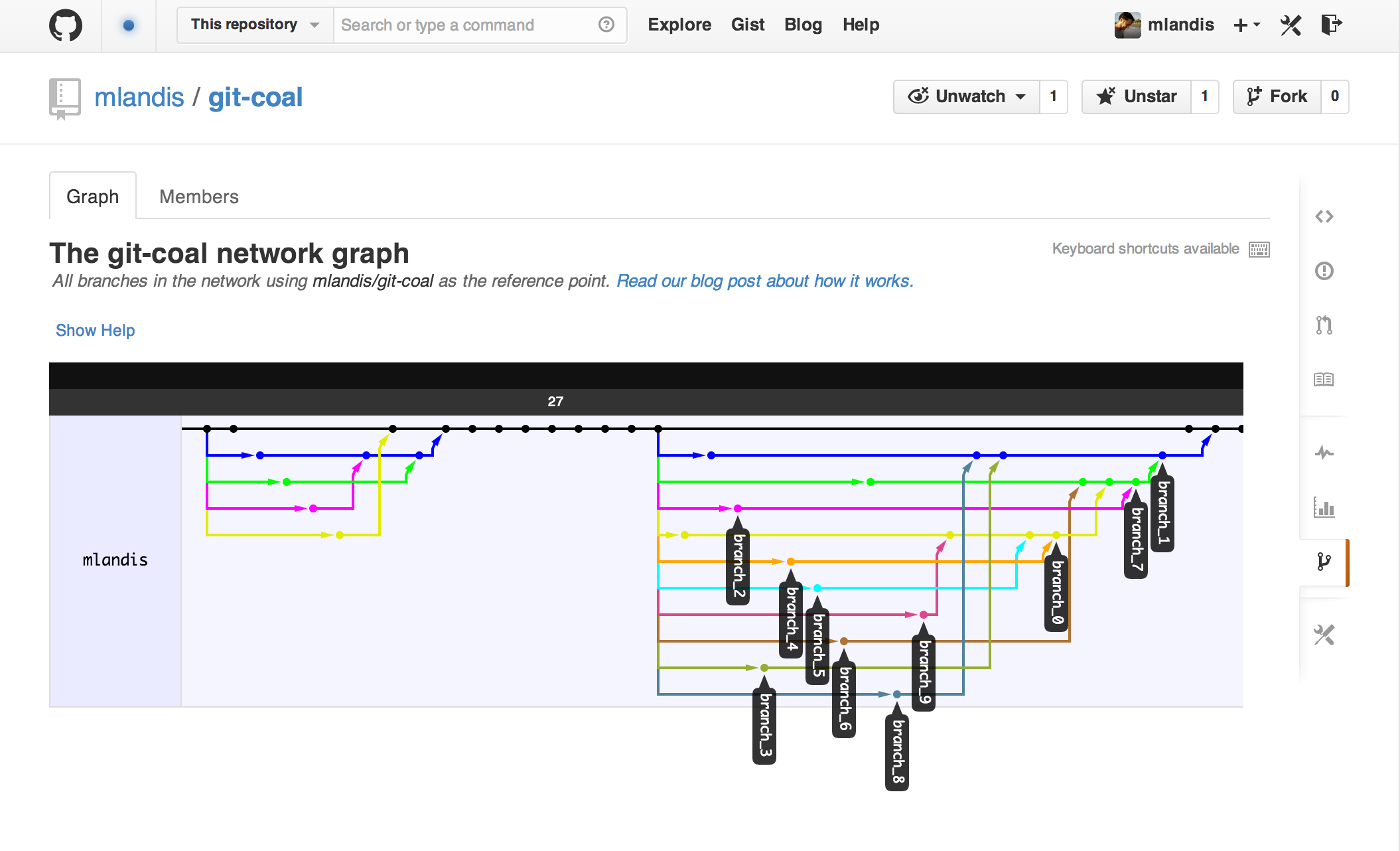

What’s more, git-log reports the entire history of branches, merges, and commits in the repository. Each event records both the SHA-1 hash key assign to itself and to its parent. Treating events as nodes and the parent-child relationships as edges, a repository’s history is a directed acyclic graph (DAG). Here’s an example of a git-DAG I simulated then pushed to http://github.com/mlandis/git-coal:

Evolutionary biologists also study a sizeable project with concurrently working contributors and complex contribution schemes. What might we learn about the “biodiversity” contained within version control system repositories? For instance, how might we model the branch-merge-commit process of a git-DAG?

Searching online, I couldn’t find many examples of probabilistic models of version control system evolution. So, I began by modeling a git-DAG using a simple continuous-time Markov chain. Our process value, , equals the number of branches active at time , and undergoes transitions, , according to the instantaneous rate matrix

Each active branch undergoes a branch, merge, or commit event at rates , , and respectively. Unlike phylogenetic inference, where the evolutionary history shared among a group of taxa is unknown, we know exactly what happens and when from git-log. This means we don’t have to integrate over unobserved intermediate git events.

The probability for an observed sequence of competing exponentially-distributed events is easy to compute. We take the initial state and time (in our case, this is and ). Then, proceeding one event at a time, we compute the probability that an event of any type occurs given the chain is in state , which is

where

is the rate moving away from the current state, times the probability of the next event being of type given the chain is state , given as

which simplifies to

The likelihood of a sequence of timed git events is simply the product of these stepwise probabilities. (There is typically a final term to compute the probability that no further events occur given the time of the final observed event. I decided to omit this factor since many git projects are intensely active then go dormant for years on end.)

To infer the parameters of this process, I set up a slapdash Markov chain Monte Carlo implemented in Python and found at https://github.com/mlandis/git-coal/blob/master/git_dag.py.

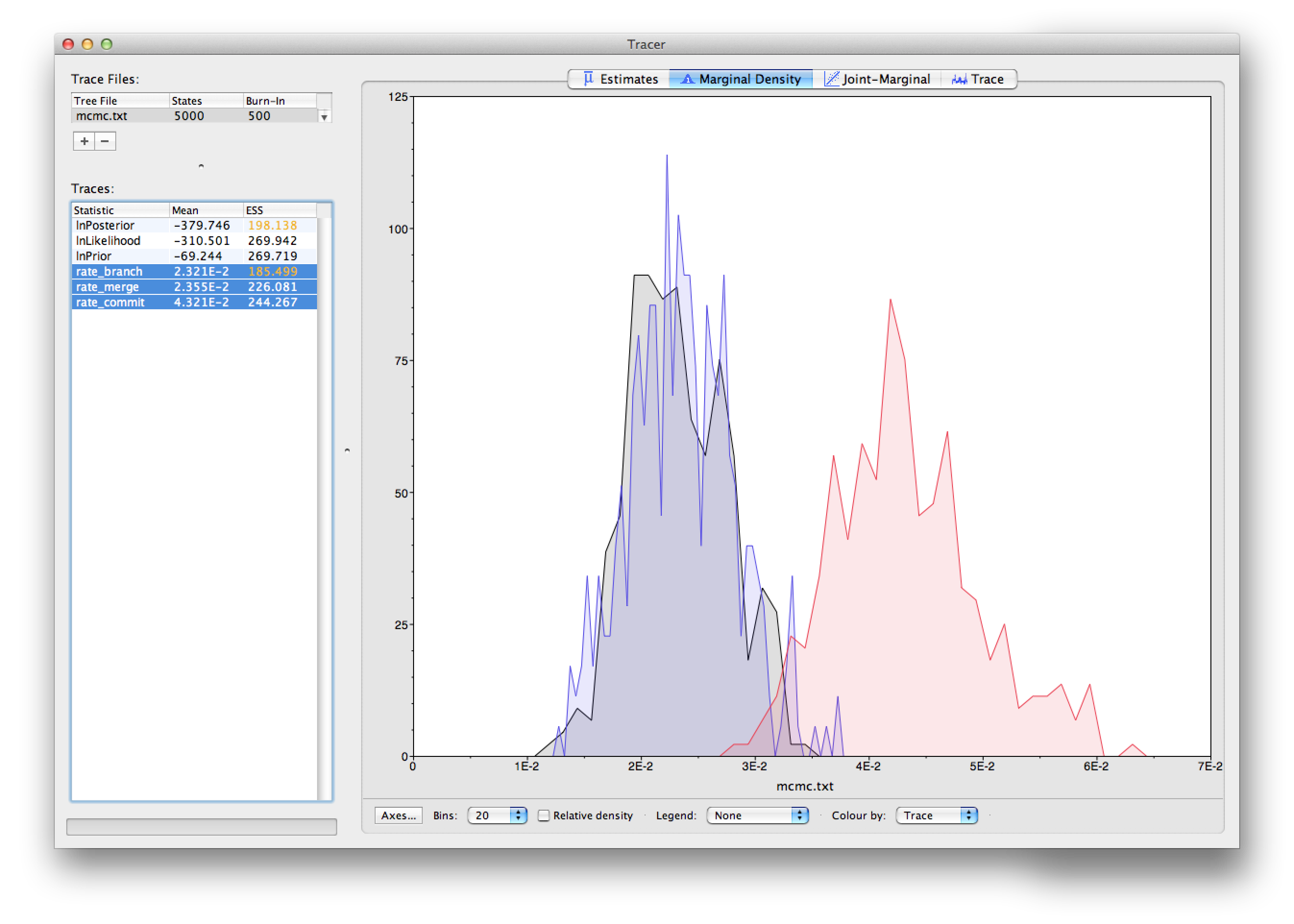

Finally, I applied this model to a simulated git-log history. Looking at the posterior from the analysis using Tracer, we see the rate of branch and commit events are approximately equal (which is true under my simulation settings).

Many disregarded factors should affect the rates of branching, merging, and committing, such as who the user is, the absolute time (e.g. of day or year), which branch is being worked on (e.g. master vs. patch), the distribution of commit sizes, which files are checked out, etc. Since git-log retains records for all these variables, they can be modeled as affecting the event rates very easily.

I’ll be playing around with this more in my spare time, but that’s all for now.